What Is User Concurrency

What Is User Concurrency

We will define User Concurrency or “Concurrent User” within the realm of SPE (Systems Performance Engineering). A Concurrent User is a user who is –

- Connected to the system

- Logged into the system

- Performance an action or

- In between performing actions

A Concurrent User is thus defined as a user who is responsible for consumption of compute/network/memory/storage resource simply due to the fact that he/she is logged into the system. This Concurrent User could either be in a state where he/she is performing a given action or is in between performing actions also called as “Think Time“.

As you’ve seen Concurrent Users are those that are connected to a system but needn’t necessarily be performing actions all the time. Concurrent Users are one of the main considerations when designing and building systems from a Non Functional Requirements standpoint.

Why Do We Need To Define User Concurrency

Defining User Concurrency is a basic requirement when it comes to designing, building and optimizing systems. User Concurrency definitions and limits are part of the systems documented Non Functional Requirements. Business within an organization generally uses the Non Functional Requirements document to communicate to the Technical Architect or Solution Architect the overall expected User Concurrency. The concurrency levels for a given system will drive various choices with regards to design patterns, architecture patterns, solution components, products, infrastructure choices, etc.

Systems with low levels of concurrency will generally (there could be exceptions here) not be built to be highly scalable unless there was a real business need to do so i.e. A POS (Point Of Sale) system within a store that is being used by 10 users (concurrent) wouldn’t need to be designed, build, Optimized, Performance Tested for 100K users. You simply won’t expend the energy and invest the resources to engineer such a system to meet high concurrency levels because the business case just doesn’t exist.

On the other hand if you were designing a Web Based Shopping Cart for a large online retailer you could be talking about user concurrency from 100’s to 1000’s of users or probably higher depending on the scale of the business and the strength of it’s brands. The design choices including choice of solution architecture, infrastructure components, application components, underlying products would all be geared to ensuring the system meets the expected user concurrency. There is a strong business case to build and engineer a system to meet the expected volumes.

How Does A Concurrent User Differ From A Named User

Named users are generally considered be registered users i.e. users who have registered to be used by the application or system. Named users differ mainly from the perspective that a Named User has the ability to access the system but isn’t currently accessing the system. As soon as a Named User accesses the system and generates a session the user now is considered to be a Concurrent User who will be performing actions (or in between performing actions) and thus responsible for consumption of system resources.

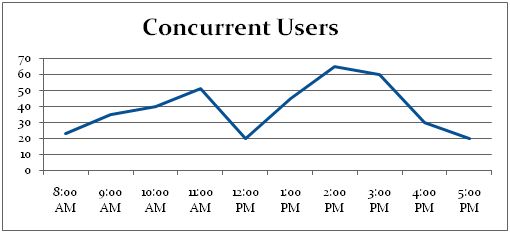

Modelling User Concurrency

Understanding User Concurrency is just the start. Being able to model User Concurrency so that you can convince yourself as a SPE (Systems Performance Engineer) that the Non Functional Requirements business has given you really make sense is highly critical. You obviously, don’t want to be in a situation where you’ve assumed the values for User Concurrency that were given to you by business only to figure out 6 months down the line that what the Business intended with User Concurrency was actually Web Server Hits obtained by looking at the Apache Web Server Logs. Systems Performance Engineers and Performance Architects have traditionally used the Operational Theory derivative i.e. Little’s Law to model User Concurrency.

John Dutton Conant Little, is an Institute Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, best known for his result in Operations Research, Little’s Law. Littles law is truly amazing in its simplicity and can be used to describe the most complex of systems including resources within those systems. Using very simple inputs which can be easily obtained by speaking to business and in some cases also obtained from your production environment (i.e. by looking at your analytics t0ols, web server/app server logs, and monitoring tools) you can obtain a view of the various quantities that are required to model User Concurrency.

Lets take for example the web based retail system described above. The notations used include:

- N - Number of users present within the system

- C - Number of completions

- X - Throughput or Rate of Departure

- A - Number of Arrivals

- L - Rate of Arrival

- Rt - Time spent by Customers within the system

Littles Law basically states that the long-term average number of customers in a stable system N is equal to the long-term average effective arrival rate, L (Lamda) multiplied by the average time a customer spends in the system, W or Rt, or expressed algebraically:

- N = L * Rt ……………….. [ N = Number of Users in the System, Rt = Response Time, L = Arrival Rate ]

Littles Law can also be stated as:

- N = Rt * X ……………….. [ N = Number of Users in the System, Rt = Response Time, X = Throughput ]

For a system where Zt (Think Time is Non Zero) Littles Law can be stated as:

- N = [Rt + Zt] * X ……………….. [ N = Number of Users in the System, Rt = Response Time, Zt = Think Time, X = Throughput ]

Using simple modelling techniques you can now validate some of the fundamental design requirements that make up your Non Functional Requirements.

Applying Little’s Law: Now that we have just defined Littles Law lets take a look at where we could apply Littles Law and benefit from a better understanding of our systems including user behavior on our existing systems.

Littles Law can be applied to the following scenarios:

- Model Performance Testing Workload

- Validate Performance Testing Results

- Validate the Sizing Models that your Infrastructure guys have come up with

- Validate the Non Functional Requirements that your Architects have recommended

To learn more about applying Little’s Law please visit Link.

Caveats : When in discussions with customers, business, architects, developers, testers, etc. be clear on your definition of User Concurrency. You’ll be surprised at the array of definitions out there when it comes to User Concurrency. Your definition of User Concurrency needn’t necessarily be the same as what we’ve mentioned above but whatever definition of User Concurrency you use make sure everyone across your organization understands that and that you have performed all your modelling, design, build and validation of performance to meet those requirements so that the system finally is able to meet the expected business volumes.

Additional Resources

- Dr. Rajesh’s papers on Performance Testing and Performance Requirements Gathering

- Microsoft : Load Testing of Web Applications

- Microsoft : Patterns & Practices – Performance Testing Guidance

- The Server Side : Performance Engineering – A Practitioners approach to Performance Testing

- Dr. Connie Smith on Performance Engineering

- Dr. Rajesh Mansharamani on Performance Engineerirng

- Wikipedia on Performance Engineering

Hope you’ve enjoyed the content in this section at Practical Performance Analyst and have learnt something new. Please help us grow the community by taking a moment and sharing this content with rest of community using your preferred Social Media Platform (links provided below). We are looking for the bright spark and if you think you have what it takes to build and grow this community reach out to me by Sending us an email.

Trevor Warren is passionate about challenging the status-quo and finding reasons to innovate. Over the past 16 years he has been delivering complex systems, has worked with very large clients across the world and constantly is looking for opportunities to bring about change. Trevor constantly strives to combine his passion for delivering outcomes with his ability to build long lasting professional relationships. You can learn more about the work he does at LinkedIn. You can download a copy of his CV at VisualCV. Visit the Github page for details of the projects he’s been hacking with.